It’s hard to believe that just over four years have passed since I first began work on this post on 6th February 2018, a hundred years to the day from the passing of the 1918 Representation of the People Act. The media coverage of the Centenary of women gaining the vote brought Church High and its intellectual ethos to mind, in particular the 2000 Millennium tagline – ‘Giving Every Girl a Voice’. At the time, I wondered how many people would be aware that the shaping spirit of Newcastle High/Church High School – which went on to mould countless girls in its likeness – had indirect links to the Suffrage movement and, via Miss Gurney’s headship, direct links to key pioneers of educating girls and Higher Education for Women?

Suffrage is a strange word, isn’t it? Most people will know of the ‘Suffragettes’ but, until this important Centenary, I wasn’t aware there were also ‘Suffragists’, nor of the distinction between these two types of activists. Despite being an English teacher, I realised I had only a vague grasp of the word’s root, mistakenly believing it to be connected to suffering for one’s beliefs. If you’ve always known that suffragism refers to the belief that the right to vote should be extended to women, please forgive my ignorance. I now know that the word suffrage comes from the Latin suffragium, meaning ‘vote’, ‘political support’ and ‘the right to vote’. The term Suffragist, in turn, refers to a member (male or female) of the Suffrage Movement who advocates a woman’s right to vote, generally by non-violent means. Later on, militant members more violently active in the ‘Cause’ were first referred to as being Suffragettes in a Daily Mail article of 1906.

For these individuals, the fight for the right to vote in political elections was the most fundamental way of gaining a ‘voice’ for women – a thing women of today can often take for granted. It’s hard to imagine the level of frustration educated, professional women must have felt being with-held a say in their country’s political process on the premise that, being female, they lacked the intelligence, seriousness of mind and faculty of discernment to register an opinion on worldly matters. Because they weren’t men.

In time, as the Cause progressed, this more militant approach to fighting for Women’s Suffrage led to the formation in 1903 of the Women’s Social and Political Union by Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst.

From 1908, those who supported the suffrage campaign were able to show their allegiance more visibly when the WSPU adopted the now widely-recognisable suffragette colours of purple, white and green: purple stood for Dignity, white for Purity and green for Hope. The architect of the suffragettes’ key visual strategy was Sylvia Pankhurst, who was a prize-winning student at Manchester School of Art. When the WSPU was planning its biggest ever rally in Hyde Park 0n June 21st 1908, Sylvia was asked to design the event. Her brief was to devise a visual concept that was both recognisable and accessible to all, whatever their financial means. Her solution was colour-coding. The actual colours were chosen by her friend and fellow activist, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, and were subsequently applied to all WSPU activities – on banners, flags, posters, sashes, rosettes, badges, tickets, souvenir brooches and even on hatpins. Discreet support could even be offered via gemstones in jewellery.

Because of its connection with Hope, green subsequently became a popular colour for girls’ schools’ uniforms around this time. In Newcastle, although only Church High School retained this colour for their full uniform – beginning with green Tam O’Shanters in 1914 – originally the PE uniform for both Newcastle High and Central Newcastle High School was green. As you can see below, the very earliest embroidered School badge in the Newcastle High/Church High School Archives actually sports all three suffragette colours. It will have been introduced in the early years of Miss Gurney’s tenure.

All of the female educational pioneers at that time were actively involved in the Suffrage Movement, although always as Suffragists. Church High School’s most immediate connection with the leading figures in this field – all passionate pioneers – is through Louisa Mary Gurney, the School’s third Head Mistress – the only one to serve as Head Mistress of both Newcastle High School and Newcastle Church High School. Before her appointment as Head of Newcastle High School for Girls in 1902, Miss Gurney taught Mathematicss from 1896 to 1902 at the prestigious North London Collegiate School for Girls, under the headship of Mrs Sophie Bryant.

Although Cheltenham Ladies College is now the more high profile of the two, N.L.C.S. was THE trail-blazing school for girls’ education in the country at the time, founded by Miss Frances Buss, who, in time, would groom her Irish Deputy Head, Mrs Bryant, as ‘heir apparent’.

Sophie Willock Bryant proceeded to build on Miss Buss’ educational legacy, taking over the role of Head Mistress at N.L.C.S. in 1895.

The following year, she appointed a young Miss Louisa Mary Gurney to a Science teaching post at N.L.C.S. to specialise in Mathematics.

To work under Sophie Willock Bryant at N.L.C.S., the first woman in the United Kingdom to gain a Doctorate, must have been a truly empowering experience for any young teacher. By repute, a woman who ‘took an active part in every progressive movement of her time’, the N.C.L.S. staff all spoke glowingly of Sophie Bryant’s character and leadership: ‘The same respect for personality which characterised Mrs Bryant’s dealings with the girls characterised no less her dealings with the staff. She never tried to impose her personality on others. Always one felt grateful for the illumination of one’s mind by talk with her.’

Despite dying long before women actually received the vote, Miss Buss’s voice is still ‘heard’ through her legacy, an unrelenting call for the education of young ladies. Nigel Watson’s book ‘And their Works Do Follow Them’ (the illustrated story of the North London Collegiate School) notes that Miss Buss’ death was reported widely in the national newspapers. Over 2,000 people attended her funeral and the names of her pall-bearers (which included the other female educational pioneers of the time: Emily Davies, Dorothea Beale and Elizabeth Hughes) ‘reflected her standing in the world of education.’

The voice of Miss Buss’ successor would go on to be heard well beyond education, however. In 1878, Miss Buss described her as ‘bright, accomplished, energetic and earnest. She is amiable and loving and above all she has vital force.’ A forthright, open personality who never hid her passionate views on a wide range of subjects, Sophie Bryant ultimately had over 50 written publications to her name, covering the full breadth of her personal and professional passions.

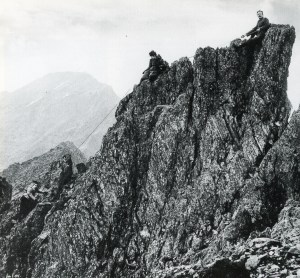

Possessing a strong Christian faith and keen interest in ethics, this brilliant scholar and influential advocate of women’s suffrage, was also an avid cyclist, an intrepid mountaineer who scaled the Matterhorn twice and an ardent supporter of Irish Home Rule, proudly wearing an orange scarf with her navy blue dress at work.

Possessing a strong Christian faith and keen interest in ethics, this brilliant scholar and influential advocate of women’s suffrage, was also an avid cyclist, an intrepid mountaineer who scaled the Matterhorn twice and an ardent supporter of Irish Home Rule, proudly wearing an orange scarf with her navy blue dress at work.

Sophie Bryant always considered herself to be a ‘suffragist’ rather than a ‘suffragette’ and, although she declined to play a key role in the Votes for Women cause owing to her professional commitments, she gave support as an occasional platform speaker at WSPU rallies.

Sophie Bryant always considered herself to be a ‘suffragist’ rather than a ‘suffragette’ and, although she declined to play a key role in the Votes for Women cause owing to her professional commitments, she gave support as an occasional platform speaker at WSPU rallies.

As one would expect of a Head Mistress, Mary Gurney was of the same mind as her mentor with regard to the more militant suffrage campaign that was raging around them. According to the Gurney Family biographer Jenny Moore, Mary believed that ‘there were many other ways to make their point’ (p. 118, ’45 Feet of Daughters’). The 45 feet of the book’s title is a reference to the fact there were no fewer than nine daughters in Professor Henry Palin Gurney’s household, Louisa Mary being the eldest sibling. Brita Gurney, three years Mary’s junior, held a very different opinion about Votes for Women. In 1911, she was arrested with other WSPU members in London for ‘stopping crowds in a park and demanding that they listen to the cause’ – at least according to her family. The Metropolitan Police Report from Cannon Row Police Station records her crime as ‘committing malicious damage’, however. She was bailed to appear at Bow Street Magistrates Court two days later, where she was found Guilty and received a prison sentence. Family documents exist indicating that, as was common amongst suffragettes, Brita went on Hunger Strike. On March 17th 1912, in case the worst outcome occured, she made a Will on WSPU notepaper. The Gurneys were gravely concerned, not least because Brita had a weak heart after a history of rheumatic fever. An ‘influential friend’ – reportedly Christabel Pankhurst, as the family story goes – was approached to intervene on health grounds. Brita was duly released, gaining her Hunger Strike Medal. What her no-nonsense elder sister felt about it all is anyone’s guess.

Nigel Watson records that Mrs Bryant had no favourites amongst her staff but, on page 44 of his history, he does mention Miss Gurney as one of six of Mrs Bryant’s Assistant Teachers (she did not believe in Heads of Department) who were encouraged by her to apply for headships with great success. A clear testament to her example. She took the training of her teachers very seriously, believing she was also teaching her staff to ‘lead’. One member of staff (Eleanor Doorly) recalls that ‘Mrs Bryant would not allow her staff to bask in a happy post. She took to putting advertisement cuttings of vacant head ships on my plate at lunch. At fist I refused to take any notice, but at last her teaching prevailed – that higher responsibility must not be shirked.’

It seems Sophie Bryant and the young Miss Louisa Mary Gurney were travelling a similar trajectory. Both held degrees in Science with specialism in Mathematics – indeed, Mrs Bryant was the very first woman to take the D.Sc., the highest degree open to men. Both were daughters of clergymen who held university-level academic positions. Both also had a strong, active Christian faith which in turn informed their teaching and their outlook on life. Sophie Bryant was a passionate mountaineer, as was Miss Gurney’s father, the Rev. Professor Henry Palin Gurney. With so much in common already, one can only imagine the impact learning her craft under Mrs Bryant at the start of her educational career must have had on Miss Gurney. And, having already lost her father to a mountaineering fall in 1904, one can only imagine her feelings during the two week search for Mrs Bryant, presumed lost in the Alps, in 1922. A tragic end to life.

Other notable aspects of Miss Gurney’s tenure at Church High can be traced back to her time at North London Collegiate School too. The high point of her headship was undoubtedly the Jubilee of 1935, with its published History, which would cement Church High’s ethos and academic reputation as one of the top girls’ schools in the North. As one of Mrs Bryant’s Assistant Teachers, Mary Gurney will have been involved in North London Collegiate School’s memorable Jubilee of 1900 which culminated in a high profile Jubilee Year Prizegiving attended by the Prince of Wales – King Edward VII from 1901- with his wife, Princess Alexandra, presenting the prizes.

A high-quality, commemorative hardback record of the 1900 Jubilee School Magazines was produced, detailing the establishment of the School and Miss Buss’s huge contribution to its successes to date. Miss Gurney will have learned a lot from this too, commissioning the publication of a history of the first 50 years of Church High School as part of the 1935 Jubilee celebrations. The front cover of the N.L.C.S. Jubilee Record features a beautiful line drawing of a small bunch of daffodils, as you can see below. Despite the Victorian love of flora, this was no random flower. Miss Buss chose daffodils as the School Flower and each Foundation Day they adorned every classroom. In a similar emblematic way, Miss Gurney chose the chrysanthemum for Newcastle Church High. They symbolise friendship and loyalty.

Having joined the teaching staff of Church High in its Centenary Year, I know there is no better way to get to know a School than by being introduced to ‘Voices of the Past’, ingrained in its very fabric. My interview took place on Thursday May 16th, which was Ascension Day in 1985. I remember that everything was running late, but I was eventually greeted with a firm, warm handshake by the Head of English, apologising that the assembly speaker had badly over-run owing to the special nature of the day. This was, of course, the enthusiastic, energetic and enigmatic Jill Mortiboys, that day sporting a smart white blazer, with the sleeves 2/3rds hitched up her arm in topical Don Johnson ‘Miami-Vice’ style! I liked the feel of this place – a quirky mix of tradition & individuality – and was ultimately delighted to find myself appointed as one of its staff. Although I wouldn’t start until the next academic year in September, it being only midway in the School’s Centenary Year, I was cordially invited to drop in for the Centenary Open Day on Saturday July 6th. I did so, of course, curious yet more-than-a-little apprehensive at the time owing to the interim nature of my connection with the School. I recall seeing archive photos on the walls of the Main Building, but spent most of my time viewing the English Department display in what was then Room 16 (the ‘Television Room’) in Tankerville House. And so my love affair with Church High began. Like many before me, I would grow into myself there and learn I had a ‘voice’.

Bibliography:

‘And Their Works Do Follow Them’: The Story of the North London Collegiate School 1850-2000, Nigel Watson, 2000, James James Publishing.

The North London Collegiate School 1850-1950: A Hundred Years of Girls’ Education, Geoffrey Cumberlege, 1950, Oxford University Press.

Frances Mary Buss and her Work for Education, Annie E. Ridley, 1896, Longmans, Green & Co.

Frances Mary Buss Schools’ Jubilee Record, edited by Eleanor M. Hill, B.A. with the co-operation Sophie Bryant, D.Sc., 1900, Swan, Sonnenschein & Co. Ltd, London.

Sophie Bryant, D.Sc., Litt.D. 1850-1922, Private Printing, North London Collegiate School.

45 Feet of Daughters, Jenny Moore, 2011, Orphans Press, Herefordshire.

Colour Decoded, Alice Rawsthorn, May 2018, The Power of Women Issue, Harper’s Bazar.

This is so well researched, Christine. Thank you very much once again for acquainting us with the people who shaped the history of Church High. Good to see this up and running again!